Saint-Jacques

Who is this great and illustrious figure that Christians go to him to pray from beyond the Pyrenees and even further afield? So great is the multitude of those who go and return that it barely leaves the roadway clear to the West.

Around 1060, an Arab emissary exclaims, according to a 12th-century chronicle

Today, as in the past, the goal of the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela is the cathedral and the Tomb of the Apostle Saint James the Greater.

St. James was one of the Twelve Apostles, one of Christ’s inner circle along with his brother St. John and St. Peter, the Lord’s cousin according to tradition. A vehement, fiery and enthusiastic apostle: “Son of Thunder” was Jesus’ nickname for him. In Jerusalem, he was the first apostle to die a martyr’s death for Christ. According to tradition, his disciples gathered up his body and took it back to Galicia, to the land that Santiago is said to have evangelized.

In the 9th century, the discovery of his tomb in Spain was authenticated by a letter attributed to a Patriarch Leo, circulated by the Royal Chancellery of Oviedo from the 850s onwards. In this apocryphal letter, inserted in the IIIrd Book of the Codex Calixtinus, the patriarch recounts the translation of St. James’ body after his execution in Jerusalem: the apostle’s disciples gathered up his body, took it to Jaffa and from there, in a rudderless boat, transported it over seven days to Padrôn, the “Perron Saint-Jacques” marking the entrance to the estuary of the Rio Ulla in Galicia. According to legend, the region was ruled by the noble Louve (Lupa) who, before allowing them to bury their master, sent them to face various trials. Having defeated a dragon and made two wild bulls docile, the disciples, Theodore and Athanasius, converted Louve and her people, and finally buried Saint James where he was discovered by Theodemir some eight centuries later.

It’s worth pointing out that throughout the Compostela route, Santiago is represented not so much as the saint who invites us to meet him in the basilica, but as the leader of all pilgrims, inviting us to take to the road in his wake. Wearing his pilgrim’s coat, his bumblebee, his shell and his pouch, he urges us to leave our comfort zone, to break with our habits, to look “further afield”: Ultreia! In fact, in Arles as in Santo Domingo de Silos, it may be Christ himself who is portrayed as a Compostela pilgrim, or Our Lady, as in Pontevedra’s so welcoming Pilgrim Madonna. Proof that for the pilgrims, the journey itself was more important than the destination.

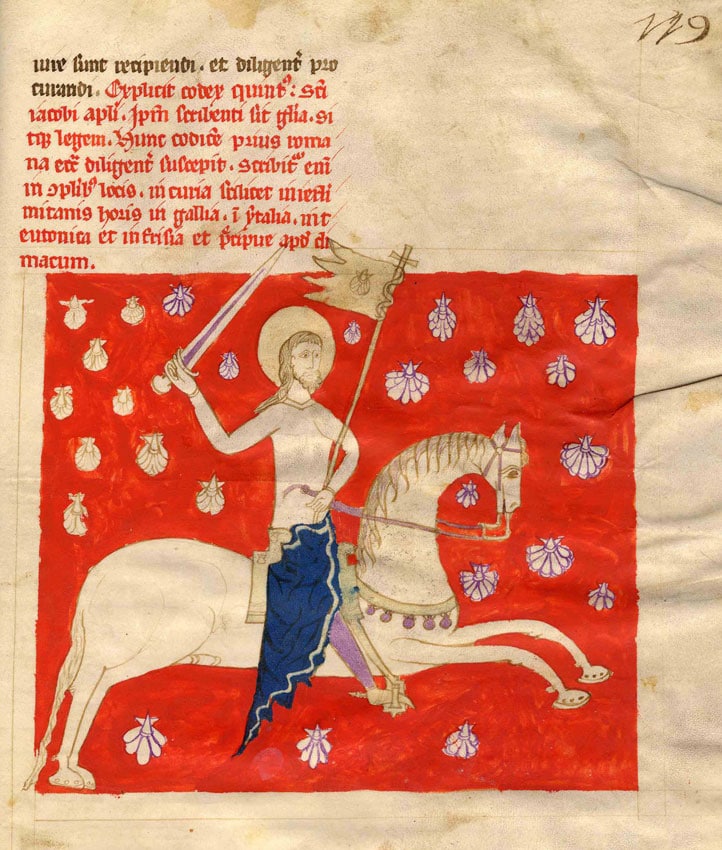

Representations of Saint James have varied over time, but the appearance of a new “image” of the apostle has never meant the disappearance of the previous ones, which coexist with it and continue to evolve:

The Apostle

The earliest depictions of Saint James show him as an apostle among others, dressed in a long tunic, barefoot, and usually carrying a book in his hand, symbolizing faith and divine will. Romanesque artists depicted him as a man in the prime of life, with a beard and wavy hair, and sometimes sandals. In the 13th century, the staff he carried – and gave to the magician Hermogenes – became a sword, symbolizing his martyrdom. It was with this sword that the articulated statue in the monastery of Las Huelgas de Burgos knighted the kings of Castile in the 14th century.

Le Pèlerin

From the 12th century in Spain, and from the 12th century in France, the figure of the pilgrim Saint-Jacques became established, recognizable first and foremost by the bumblebee and scarf, i.e. the staff and sack that pilgrims receive at the investiture ceremony. He also wears a wide-brimmed hat, sometimes a calabash, and shells decorate his bag or hat. In 14th-century France, his highly distinctive attire made him resemble a sage, a man of dress and knowledge. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the apostle would be depicted in the clothing of the pilgrims of the day.

Le Matamore

The depiction of St. James as a horseman, mounted on a white horse and treading on one or more defeated Moors, recalls the legendary intervention of St. James at the Battle of Clavijo: this image first appeared on a Compostela church portal in the early 13th century. The story of the battle of Clavijo (834 or 844) was invented in the 1160s to justify the payment of a tax to the apostolic shrine, the “Vows of Santiago”, promised by King Ramire if the apostle gave him victory. The image of the matamoros (Moor-killer) or “matamore” became firmly established in the Modern era, when Spain had rid itself of the last Muslims on its territory, but the Turks were threatening the West. Adopted also in Flanders and Hispanic America, where St. James became the destroyer of paganism (i.e. unbaptized Indians), it symbolized the militant Catholicism of the Counter-Reformation. From the end of the 15th century, Saint-Jacques Matamore holds a sword in his hand and is often adorned with the pilgrim’s attributes: hat and shells. In the 16th century, he was sometimes dressed as a knight of the Order of Santiago.

With what respect should this holy place be honored, where the most holy body of the Apostle is kept, who had the good fortune to see and touch God made Man!

we read in the Livre de Saint-Jacques